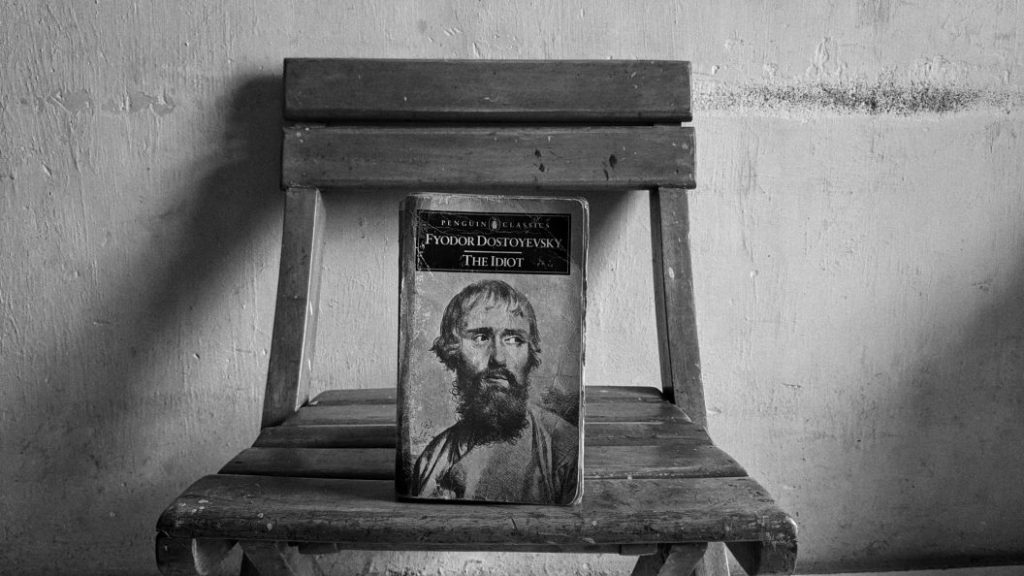

The Idiot.

Fyodor Dostoevsky’s existential beast is often misinterpreted or easily dismissed given the blunt title. The whole book sways and pivots on the protagonist and hero Prince Lev Nikolayevich Myshkin.

Dostoevsky said he wanted to depict a “completely beautiful human being” in the image of Christ himself. Myshkin is one of the most loveable, endearing, beautiful characters in literary history but it’s not because he’s modelled on some virginal, lustless, pious, deity. I mean, JC might have been a friend to the outcasts but given he hung out with prostitutes, tax collectors and drunks, it’s hard to imagine he didn’t succumb to the temptations of the flesh.

So what truly makes Myshkin such a god-damn, evocative and captivating character, is he is probably literature’s first anti-hero.

It has been 30 years this month since I first opened the pages of the book. And as comically absurd as this is going to sound, the novel changed the trajectory of my life.

But can one single book really have that much of a fundamental impact on us?

I reckon it can.

I will happily admit there were a number of contributing factors to why the book has left such a sizeable imprint on me.

I had just embarked on a nervous, poorly mapped-out trip to Europe, in an attempt to vacate myself from, well, myself. I was going through my own hellish, existential stew, trying to kick the habit of being a Catholic.

It’s harder than you think.

The Catholics have a decent smorgasbord of guilt, so it takes some serious scrubbing to cleanse the body. The Catholic’s might rank pride as their number one sin, but I believed there was a hard, metal, foldout chair in hell waiting for masturbators like me.

While the the last remnants of my faith were making me feel deeply alone, defective and rigid, The Idiot did the opposite. It struck a calculated blow that propelled me away from the puffed-up authorities of the church and the suffocating rigidity of following a set of rules.

And one final critical ingredient has added to The Idiot’s lasting legacy. Little did I know, but where I read the final pages was the place where the Christians played their first game of hide and seek from the Romans. That comes later.

You can find a more astute analysis of The Idiot online by folk that know a hell of a lot more about the book than me. I could craft some half-arsed, literary examination of the novel, but there is a good chance I’ll get it wrong.

Here is the shortest summation of why the novel is so achingly beautiful; Myshkin.

He’s an unbearably shy, 26-year-old, who has all the sex drive of a Giant Panda, despite four female characters in the book wanting to marry him. Ok, they want to marry him out of pity. Myshkin has just spent four years in a nuthouse in Switzerland getting treated for epilepsy, surrounded by a vast array of 19th-century diseases that could possibly kill him at any moment.

He has a Tourette-like approach of telling the awkward truth about other characters and himself and often carries on about how donkeys cheer him up.

His new best mate, Parfyon Semyonovich Rogozhin, has just inherited a bucket load of money from his father and just happens to be recklessly obsessed with the heroine of the book Nastasya Filippovna – who Myshkin desperately wants to ‘save’. Rogozhin is instantly fascinated with Myshkin, then spends a considerable amount of time fantasising about killing him.

The exquisitely beautiful, yet self-destructive Nastasya is murdered by Rogozhin, who is sent to prison. Myshkin is driven bonkers by her death and Rogozhin’s sadistic stalking of him so is shunted off back to the madhouse in Switzerland.

Yeah, the novel is drowning in suffering, despair, illness, depression, suicidal tendencies, romantic betrayals, alcoholism, poverty, and death.

Dostoevsky’s excruciating plummet into the human condition – well let’s be honest, the male condition – can be a hard Sunday roast to swallow. But the endless suffering is just one layer of the book. It is balanced out with beauty.

And what a hauntingly beautiful, intriguing character is Nastasya.

Female characters weren’t exactly front and centre in 19th century literature written by men who had a few religious hang ups, but Nastasya might be the odd exception. She is vulnerable, beautiful, exotic, smart and mildly unhinged. It wasn’t difficult to see why I fell in love with her.

But there lies the brilliance of Dostoevsky; he has made millions of men and women fall in love with Nastasya. And probably made the same men and women fall deeply in love with Prince Myshkin.

As I mentioned previously, the novel has left an incalculable, endless mark on me because of where I polished off the book.

Ok, there are some shallow connections but I would argue they’re important: I was the same age as Prince Myshkin. I dressed like a foreigner and acted like an idiot in most social outings, particularly in front of women. And there was that existential thing with God.

I was catching a bus from Ankara in Central Turkey to Goreme, in the historical region of Cappadocia. I still can’t remember why I went to Ankara but I knew Cappadocia was surrounded by these surreal, towering rock formations called ‘fairy chimneys’. The whole region was blanketed by ash from ancient volcanic eruptions which later solidified into a soft rock called ‘tuff’. It is believed St Paul built his first church in Cappadocia, which was quickly followed by the first ever brothel.

Travelling on a bus in Turkey in the early 1990’s was a terrifying experience. I expected the vehicle to skid off the road at any moment and go bouncing down the side of a mountain. Even If I did manage to crawl out of the wreckage and drag my broken, blood-soaked body to safety there was a good chance I’d be eaten by a Brown Bear. The coast of Turkey was relatively unspoilt then, but whatever wildlife remained was getting chased out by the endless line of new hotel constructions.

The seats and armrests on the bus were caked in 40-plus years of Camel cigarettes. Camel cigarettes contain Turkish tobacco and the Turks regarded them as critical to their diet. If the vehicle suddenly burst into flames it would cover the nearby towns in a bloom of tobacco smoke for weeks. I was positive there was a place along the route to Goreme where they discarded tourists’ bodies that had succumbed to smoke inhalation.

I had found a seat near the back of the bus after navigating my way past 30 or so families, thrusting poorly-tied sacks, suitcases and children into any space they could find. It was nudging 40 degrees outside but the interior of the bus was made even more summery by the Turk’s peculiar obsession of wearing wool jackets. The Turkish also don’t seem to like open windows. I’m guessing it was so they could embrace the full benefits of second hand smoke.

I momentarily eye-off what looked like a small air vent on the roof but was paranoid that I might release some insects that were likely to paralyse me.

As I was trying to breathe through a small crack in a window, a family of five started mulling over whether to sit next to me. I could sense my soon-to-be travelling companions were terrified I had just escaped from the UFO religious cult, Heaven’s Gate.

I was wearing khaki army shorts, a Billy Bragg t-shirt and Doc Marten boots. The raggedy beard and afro only added to my sect-like appearance.

The husband nudged and poked his three kids at the base of my feet, like he was stoking a fire.

The bus driver had barely crunched into third gear when the smallest child started vomiting all over my Docs. I found myself heaving and dry reaching every time the pint-sized puker, disgorged himself onto the only pair of shoes I had.

The annoyance I felt was unjustifiably dumb. Looking back I should’ve been more sympathetic to a family that couldn’t afford the money to buy more than one ticket. My world view needed widening.

There was nothing else to do on the bus trip so I set about finishing The Idiot surrounded by a dense fog of nicotine. It was night, so the only light was a one-watt bulb that barely illuminated a sentence or two. I appeared to be the only person awake, with the exception of a couple of men behind me, whispering ‘we must kill the Western infidel who worships this Billy Bragg’.

Then I went to turn a page and it was blank. I mean, I should’ve seen the end coming given one of the last lines in the book: “We’ve had enough of following our whims; it is time to be reasonable.” Given the murder, betrayal, suffering despair and dread, it seemed like a decent idea.

And as I closed the book and gazed around the bus, I let out one of those sincere chuckles that rarely visit us when we are alone. It was a reawakening.

I was tempted to ask the bus driver to pull over and just abandon me at the next village, where I’d set up an Idiot cult.

Then the man sitting next to me suddenly jolted awake as if remembering he had another child in the overhead compartment. He got a glimpse of the book in my hand and started squealing Dostoevsky’s name again and again. I was trying to work out if he was a fan of the novel or if his father was killed by Russian Cossacks. He even kicked his sons awake and pointed to the novel as if it was some divine text his kids should know.

I had absolutely no idea what was unfolding but I knew it was magical and unforgettable. It was happening to me. I knew this was a feeling I was never going to recapture trying to find God in a church. For the first time, I no longer felt adrift and hopeless.

In the darkness I could just make out the dream-like structures of the ‘fairy chimneys’. If Christ was going to make an appearance, this was the place.

Now, if I had finished the book on a wet Sunday afternoon in Perth would’ve I experience the same reawakening? There is a chance I could’ve jumped into my unlicensed, 1973 Volkswagon and driven around to a friend’s house, manically screeching: “I’ve just read the greatest fucken book of all time? “You need to stop what you are doing right now and read this copy I bought you five minutes ago from a second hand book shop. You are almost guaranteed to have a minor breakdown on the completion of the book, but don’t panic because you will emerge a better adult”.

Did the agonising silence of the smoke-filled, aging bus make the book more seductive and powerful? Undoubtedly.

The Idiot taught me that you can’t afford suffering and despair. But Dostoevsky showed me the beauty of writing. No book I have tackled since, and I like to think there has been a few thousand, has left such an indelible mark on me as The Idiot.

It is the book that changed my life.

Leave a comment